You got CSS in my Javascript

I switched my website back and forth between SCSS and Styled-Components four times. Here are some thoughts on why I couldn't make up my mind and why I eventually chose what I did.

Skip To Content

SCSS is magical. As someone who learned web development through the front end, seeing things like nesting, variables, and mixins were game changers for me. With the addition of learning BEM — gone were the days of having a monolithic, hundreds-of-lines-long .css file and a new age of writing maintainable component libraries was laid out in front of me.

Fast forward a few years to when I was in the middle of converting my personal site from Jekyll to Gatsby. CSS-in-JS is a divisive issue in the web-dev community right now, so I decided to try out 💅 Styled-Components in order to have a more informed opinion.

The internet probably doesn't need another hot take on which approach is better, but here comes one anyways.

The Allure of JavaScript in the First Place

One of the first concepts you learn when getting into maintainability and best practices is to separate your concerns. You don't want your frontend code mixed in with your backend logic, your content mixed with your display templates, or your styles mixed in with your structural markup.

But is that last part really still true?

One thing React stresses in its documentation is to think in components. This means often times you will have logic on when to display components and onClick handlers in the same file as your JSX. What makes styles different? If you're concern is the overall display, why have these rules live across multiple files?

And to the point of having display logic already in your JSX files, why not go one step further with this? Having to style something as display: none because you want to hide it at a certain size always felt kind of lame to me. I'm sure this has performance implications as well, because the browser still has to parse this markup before deciding not to render it, and the markup still exists in the DOM. I'm also pretty sure if you're in a situation where you have both a desktop and mobile version of a component in the markup, encountering both on the page while using a screenreader is somewhat of an accessibility concern.

In my project I have a config.js file that looks mostly like this:

module.exports = {

breaks: {

large: 1200,

tablet: 768,

phone: 480

},

}I did some research around using Redux to track browser size as part of my site's overall state, but using Redux to store only a handful of thing seemed like overkill. Alternatively I settled on using react-responsive. This means that instead of having to render my mobile nav and hide it with display: none, I can just wrap it in a <MediaQuery> tag and not have it as part of the page until I need it.

<MediaQuery query={`(max-width: ${breaks.tablet}px)`}>

<Navicon />

</MediaQuery>Using this same configuration style, I was able to pull these values — as well as colors and fonts — directly into styles that lived right next to the markup for the component itself, and use the same SCSS shorthand I was used to.

const StyledSocials = styled.ul`

.social {

width: 1.75rem;

display: block;

@media(max-width: ${breaks.phone}px) {

flex: 1;

width: auto;

}

}

svg {

fill: ${colors.white};

@media(max-width: ${breaks.tablet}px) {

fill: currentColor;

}

}

`Also, if I ever stopped using a component and decide to delete it, this would take the styles with it instead of leaving them in another file elsewhere in the project. I know there's tooling around this, but I personally am always hesitant to delete styles on the off chance I want to use them again in the future. Another reason, to be honest, is that I'm also not always sure where else in the project I might be unknowingly using that style (I should be doing visual regression testing, I know).

Recovering a deleted component from a single file is so much easier than having to retrieve markup and styles from multiple files in my git history. This made me much less hesitant to remove unused components and take everything associated with them out of my project at once.

Why switch so many times?

In coding, I often face choice paralysis. I spend so much time doing research to make sure I won't have to start over midway through a project, and in an effort to avoid that I unintentionally did the opposite. Instead, I decided to pick something new and go with it, and I ended up jumping between branches and copying a lot of code every time I would run into a new barrier or find a solution to one.

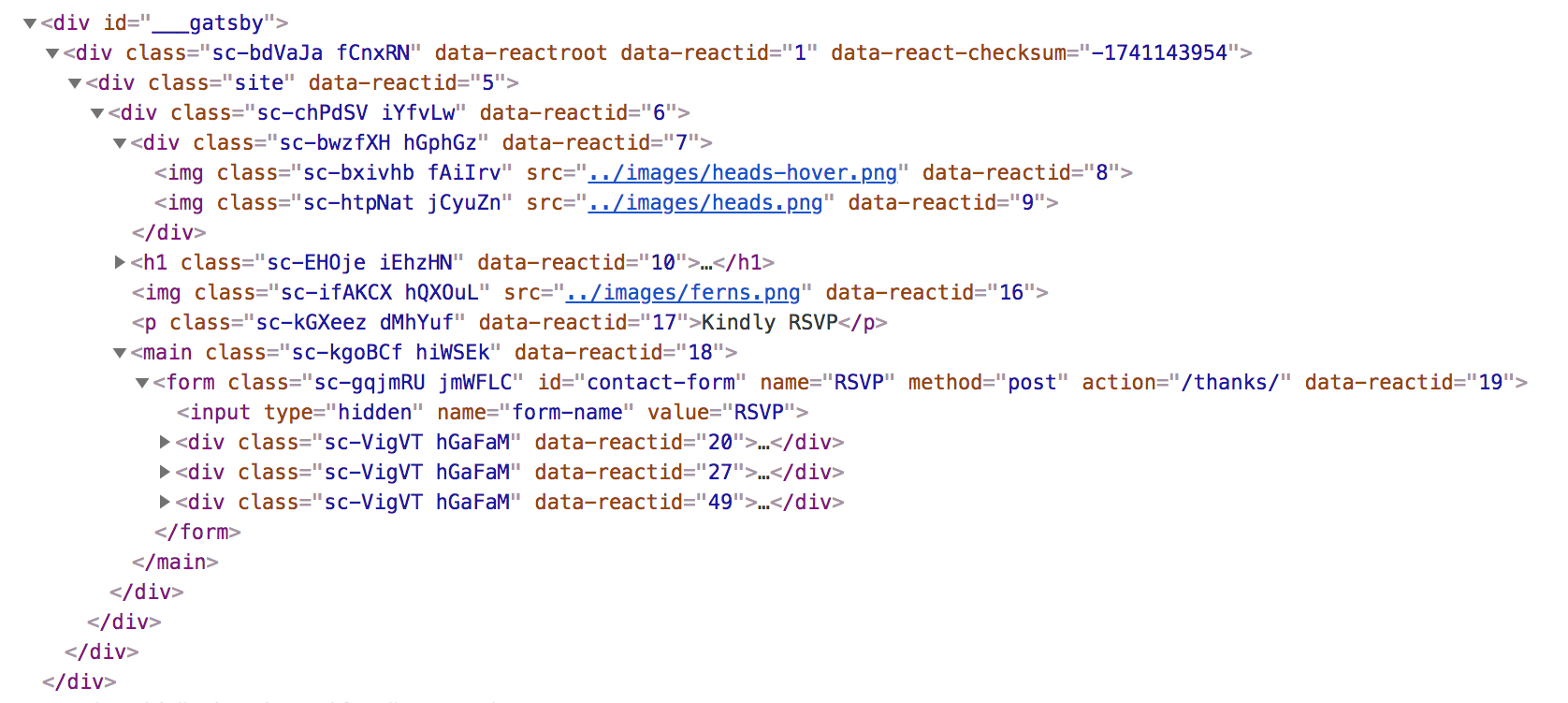

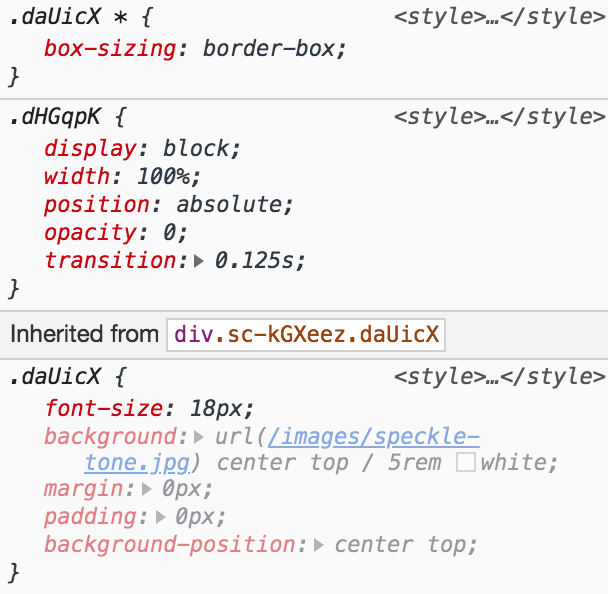

The first and most obvious frustration was debugging. The way Styled-Components (and I think most css-in-js libraries?) handle the issue of scoping is to generate machine-readable classnames and apply them to the JSX elements. That means, in the browser, you end up with a lot of nonsense as far as human-readability is concerned.

You can add your own classes, but if you're correctly leveraging the power of the scope and cascade you shouldn't be afraid to just style based on elements.

const Container = styled.div`

max-width: 40rem;

img {

width: 100%;

}

`;

const Hover = styled.img`

opacity: 0;

transition: .125s;

&:hover {

opacity: 1;

}

`;

const Image = () => (

<Container>

<img className="hover" src="../images/heads-hover.png" />

<Hover src="../images/heads.png" />

</Container>

)

This is great and very readable while authoring code, but it makes debugging in the browser very hard. I'm sure there are ways to set up sourcemaps, but by default there's no easy way to see where a style is declared in your project. It's easy enough to track down a top level bug since its probably obvious which component the style is coming from, but specificity is still a problem when components are nested. Rather than being self-documented in the browser with classnames, this required keeping the location of styles in mind while working. This is especially difficult when coming back to a project weeks or months later.

Another downside to the mental model required here is that even though these styles are written in javascript and use javascript syntax they still boil down to css using css syntax. This means using and understanding a lot of extraneous code just to compile the final product into a format that will work.

$tablet: 768px;

@mixin tablet-break () {

@media only screen and (max-width: $tablet) {

@content;

}

}

---

@include tablet-break {

//styles

}In order to replicate this relatively simple SCSS mixin (above) in Styled-Components we need to define a break size, write a function to scope styles to that breakpoint, and then call that function in a component.

export const breaks = {

tablet: 768

tabletBreak: (styles) => {

return `

@media (min-width: ${breaks.tablet}px) {

${styles}

}

`

},

};

---

import { breaks } from '../styles';

const StyledDiv = styled.div`

${breaks.tabletBreak(`

// styles

`)}

}

`;Because using style-components means writing in one language and interpreting in another, this requires weaving in and out of javascript syntax and css syntax. Thankfully ES6's template literals make this really easy, but this still requires a developer to hold a lot in their mind. In just this one breakpoint I'm defining a function, returning a string to be converted to css, calling a javascript variable, passing an interpolated string into the function, calling the initial function in another file, and then finally passing ing styles via another template literal. Nevermind if it's necessary to call some other javascript variable inside that string of styles. One small syntax error here means trying to track down a stray ` or ) or { across multiple files.

Further to the point of having to overcomplicate things that SCSS natievely does with relative ease, SCSS is a very mature language with over ten years of stability and nuance behind it. The web developer community has had time to make improvements over the years, and while I'm sure the css-in-js community as a whole will eventually get to that level, right now there's just too much missing. SCSS functions I've taken for granted like transparentize() or the ability to easily do math with values of different units like ems, rems, and pixels (without having to work in either npm dependencies or complicated interpolations) is a hard thing to give up.

These are all solvable problems, but the one thing that there's no way around is that these styles only live in javascript. If the project at hand isn't one entirely in javascript a lot of the ideology that makes css-in-js great starts to fall apart. Both at my current and previous jobs, numerous projects exist as a mostly standard web application with only one of the more dynamic pieces written in React. Opinions on the validity of this practice aside, there is simply no way to share the styles from a StyledButton component in a way that will also have them hit your regular html .button class. In most cases where you won't be starting from scratch on a project, it might not be worth the time to convert a businesses entire design library into components, nor may it be possible without ending up maintaining styles in two places.

Does either solution solve all of the problems?

Yes and no.

One of the biggest reasons I've heard for switching to css-in-js is that it will solve the problem of globally scoped css. Is this really a problem though? It never has been for me. Proper use of BEM makes it very easy to scope elements to their appropriate block. Even when not using the BEM syntax it's easy enough to wrap something in a top level class applied to the html body or a component.

.button {

background: $orange;

}

---

.form {

&__button {

background: $blue;

}

.button {

background: $blue;

}

}

---

body.form-page {

.button {

background: $blue;

}

}BEM aside, taking advantage of SCSS's native ampersand ability gives you just as much power as Styled-Componen'ts theming functionality.

.button {

background: $orange;

.form & {

background: $blue;

}

}Not as many people know about putting the ampersand after the nested selector in SCSS, but this is a great way to add styles to components only when they are used on certain scenarios inside of other components. The above code will compile to the following CSS

.button {

background: orange;

}

.form .button {

background: blue;

}One thing I've been interested in is viewing pages with no css at all. If you're writing minimal semantic markup your site should still work decently with no styles at all. Maybe you need some critical css just so the retina sized images aren't blown outside the bounds of the page, but heading and paragraph tags should still render a readable site. With this in mind, is it fair to treat the entire frontend as one single concern when the markup rendered to the DOM needs to stand alone? Of course, this is a bigger issue when rendering entire pages in javascript all together, and how things appear in the browser do not necessarily need to be one-to-one with how a developer authors the code.

One downside to viewing the DOM without any styles is that an end user sees everything on the page — including things like incorrect canvas navigation or different versions of components shown at different sizes. Also, there's nothing to stop you from using both scss and react-responsive, which is actually what I settled on doing. This means that even if viewing the page with css turned off, a user will still only get one navigation and one version of a component unless their browser is at the right size to trigger a <MediaQuery/> tag. The downside to this is that I need the breakpoints configured in two places: once in my config.js object and once as traditional scss variables somewhere in the style files. I'm sure there's a way to make one read the other (probably to have the .js file pull from the .scss file?), but the amount of work to do this didn't seem worth it in my experience. Luckily, these configuration values rarely will need to be updated so this isn't a dealbreaker for me.

Overall, I still see the appeal of putting componentizing styles in javascript. Im my opinion, there are huge workflow and browser performance gains to be made, and as libraries and functionalities grow over time, switching to them won't mean leaving as much behind. For now I'm sticking with SCSS because that's what my current job requires me to write. Additionally having a personal project where I can continue to explore more complex mixins and extends will only help me become a better developer. Knowing myself though, I'm sure the next personal project I start from scratch will convince me to do something completely different, because the idea of leveraging the ability to have code more and more integrated with itself is definitely tempting. However, as long as future projects continue to be as much of a learning experience as the back-and-forth switching on this project was, I'll gladly be along for the ride.